Webster's Dictionary (at least the version I have) states that pathos means, "the quality in something which arouses pity, sorrow, sympathy, etc." This concept has intrigued me for quite some time. I've heard many people refer to the word when it comes to entertainment. Disney animators talk about how it makes up the core of their character animation. John Kricfalusi has said that Disney films are full of fake pathos. How does one tell the difference between "Fake Pathos" and "Genuine Pathos"? Well let's take a look at different examples of pathos in the media, particularly film, and film animation.

Jim Smith, animator/manly cartoonist, has described his definition of pathos as, "Emotional content, not just sadness or sentiment, but honest emotion as opposed to contrived."

Mr. Smith, while discussing the topic with yours truly, has cited the classic comic strip "Popeye" by E.C. Segar as an example of genuine pathos. For example, in one strip, Popeye gives money to an orphanage because he was once an orphan himself. Jim Smith gets a manly lump in his throat every time he reads it. Sorry I couldn't find the matching picture, but spanking can be a source of pathos, as it is a common experience to children, representing a parent's disapproval.

Mr. Smith has also mentioned the beloved Christmas classic "It's a Wonderful Life" as a strong narrative with genuine pathos. In particular, he cites the line "Zuzu's petals" as a tearjerker. I have nothing to argue against it (since I've never seen it), so I'll go along with it. It seems that even some of the most bitter of curmudgeons are moved by this story. I'll attribute that to a great performance by Jimy Stewart and wonderful direction by Frank Capra.

Now, what is an example of "fake pathos"? The best example I could find is the story of The Vampire's Assistant. I remember seeing this with my cousin while we were at a Bainbridge Island theater. It concerns two boys, Darren and Steve (pictured below). Both go to a freakshow, where Steve recognizes a vampire working for them named Crepsley. Steve wants Crepsley to turn him into a bloodsucker, but is refused for having "bad blood" (How does that work?). When Steve finds out that Darren has been made into a vampire, Steve feels betrayed and swears revenge.

We're given a bit of backstory for Steve, where it states that his parents never notice him, or some such crap, and how he feels like Darren stabbed him in the back by becoming a vampire, but there's no indication of why we should give a damn. He actually says in the movie that his friendship with Darren is secret, and he doesn't want people to know about it. All in all, I don't feel any sympathy for him, so there goes the dark but sympathetic anti-hero angle, and he's too much of a whiny dipshit to take seriously as a villain. I was praying he would have his head ripped off by a random werewolf attack. I actually got the same feeling about the characters, particularly the villain, of Meet the Robinsons.

Perhaps that's the difference between genuine and fake pathos: the strength of the story and the emotional investment in the characters. The reason why we feel sympathy for characters like Popeye is because they have endeared themselves to us, because they are strong interesting characters. For example, back in the 20s or 30s, Sandy the Dog, of Little Orphan Annie fame, was injured and no less than Henry Ford himself sent a letter to the syndicate that distributed the strip asking if Sandy would survive. That's the kind of power a good character can have on people.

Another way of distinguishing true and fake pathos is how hard one tries to get people to sympathize with characters. John K. has stated that Disney uses camera cuts and music, as well as sad background stories, to achieve pathos. I find that to be a major blunder, especially in recent animated films. Let's take a look at Meet the Robinsons again. The film tries too hard to find empathy, but the characters are so nondescript and lackluster that I was left cold. However, they used every trick Disney could use to get an emotional reaction, from the sad music to the main character's backstory as an orphan. Unfortunately, I wasn't feeling it. Too forced for my tastes. Does that make me coldhearted?

A perfect example of a film with true pathos, despite its length and lack of familiar characters, is the classic Chuck Jones cartoon One Froggy Evening. It succeeds on narrative and use of archetypes, but also because everything feels as if it occurs naturally. Even though Chuck Jones' cartoons sometimes feel as if the characters are preordained to act a certain way, the reactions feel natural. Let's take a look at our main character. He's a joe-shmoe working to make a living. He finds the singing frog and sees a way to fame and fortune, a way out of the drudgery, like all of us want. However, he is foiled at every turn by some divine interference which states that nobody but him can see the frog sing and dance.

That causes him to go from this...

To this

Tom Kenny has stated that he found this cartoon to be "existentially sad".

Tom Kenny has stated that he found this cartoon to be "existentially sad".

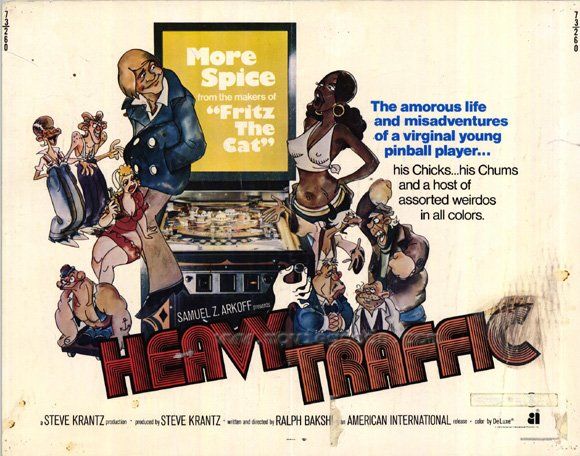

I get a similar reaction when I view Ralph Bakshi's Heavy Traffic. It seems to be the whole feel of the film. One scene in particular always moves me in way I can't quite describe. It is the scene at the nostalgic nightclub, where Michael meets up with his mother Ida. Afterwards she has a drunken conversation with him, she wanders where soon she is surrounded by old family photographs. She soon sees her old wedding photo, and finally collapses, realizing how she has wasted her life, and youth, by being married to Angelo Corleone. It's a very quiet, but powerful scene. There are no tears, but simple realization and resignation. I don't tear up, but I feel the complete despair and emptiness of Ida.

You can view it here on this clip from YouTube.

Thank you for reading my little mini-essay on pathos. I guess ultimately, pathos lies in the eye of the beholder. It's all up to you.

Now, to finish, I'm going to show you one of the few scenes in film that causes me to bawl like a baby. If you don't shed at least one tear, then you are a heartless communist.

Until next time boys and girls.

Thank you Jim Smith for the inspiration.

You can view it here on this clip from YouTube.

Thank you for reading my little mini-essay on pathos. I guess ultimately, pathos lies in the eye of the beholder. It's all up to you.

Now, to finish, I'm going to show you one of the few scenes in film that causes me to bawl like a baby. If you don't shed at least one tear, then you are a heartless communist.

Until next time boys and girls.

Thank you Jim Smith for the inspiration.